x64AssemblyLessons

Based on https://asmtutor.com/ but updated to reflect x64

Project maintained by Rubender353 Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme by mattgraham

Lesson 1 Hello, world! Lesson 2 Proper program exit Lesson 3 Calculate string length Lesson 4 Subroutines Lesson 5 External include files Lesson 6 NULL terminating bytes Lesson 7 Linefeeds

Lesson 8 Passing arguments Lesson 8-1Passing arguments 64-bit style Lesson 9 User input Lesson 10 Count to 10 Lesson 11 Count to 10 (itoa) Lesson 12 Calculator - addition Lesson 13 Calculator - subtraction Lesson 14 Calculator - multiplication

Lesson 15 Calculator - division Lesson 16 Calculator (atoi) Lesson 17 Namespace Lesson 18 Fizz Buzz Lesson 19 Execute Command Lesson 20 Process Forking Lesson 21 Telling the time

Lesson 22 File Handling - Create Lesson 23 File Handling - Write Lesson 24 File Handling - Open Lesson 25 File Handling - Read Lesson 26 File Handling - Close Lesson 27 File Handling - Update Lesson 28 File Handling - Delete

Lesson 29 Sockets - Create Lesson 30 Sockets - Bind Lesson 31 Sockets - Listen Lesson 32 Sockets - Accept Lesson 33 Sockets - Read Lesson 34 Sockets - Write Lesson 35 Sockets - Close Lesson 36 Download a Webpage

Lesson 1

Hello, world!

First, some background Assembly language is bare-bones. The only interface a programmer has above the actual hardware is the kernel itself. In order to build useful programs in assembly we need to use the linux system calls provided by the kernel. These system calls are a library built into the operating system to provide functions such as reading input from a keyboard and writing output to the screen.

When you invoke a system call the kernel will immediately suspend execution of your program. It will then contact the necessary drivers needed to perform the task you requested on the hardware and then return control back to your program.

Note: Drivers are called drivers because the kernel literally uses them to drive the hardware.

We can accomplish this all in assembly by loading RAX (EAX in x86 32-bit) with the function number (operation code OPCODE) we want to execute and filling the remaining registers with the arguments we want to pass to the system call. A software interrupt in 32-bit is requested with the INT instruction and the kernel takes over and calls the function from the library with our arguments. In 64-bit it will use 32 bit registers, so we will need to use syscall interrupt in 64-bit assembly. Click here to learn more about int 80h and syscall

For example requesting an interrupt when RAX=60 will call sys_exit and requesting an interrupt when RAX=1 will call sys_write instead. EBX, ECX & EDX is now RBX,RCX, & RDX in 64-bit x64. RBX,RCX, & RDX will be passed as arguments if the function requires them. Click here to view an example of a 64-bit Linux System Call Table and its corresponding OPCODES.

The biggest difference from 32-bit is that after RAX 6 registers get used sequentially as parameters. After that other registers will be put on stack. In 32-bit you could write hello world using RBX register to store stuff in it. In 64-bit we now need to keep in mind the 6 parameters passed by register. Which are RDI,RSI,RDX,RCX,R8, and R9.

Keep in mind I will be using Linux specifically Ubuntu. Depending on your architecture and ABI used these may be called differently. So if using nasm for some other device refer to their documentation, calling tables, and ABI info.

| Register | Value |

|---|---|

| RAX | System call number |

| RDI | 1st argument |

| RSI | 2nd argument |

| RDX | 3rd argument |

| RCX | 4th argument |

| R8 | 5th argument |

| R9 | 6th argument |

Writing our program Firstly we create a variable ‘msg’ in our .data section and assign it the string we want to output in this case ‘Hello, world!’. In our .text section we tell the kernel where to begin execution by providing it with a global label _start: to denote the programs entry point.

We will be using the system call sys_write to output our message to the console window. This function is assigned OPCODE 4 in the x86 Linux System Call Table. In x64 we will user OPCODE 1. The function also takes 3 arguments which are sequentially loaded into RDI, RSI and RDX before requesting a software interrupt which will perform the task.

The arguments passed are as follows:

RDX will be loaded with the length (in bytes) of the string. RSI will be loaded with the address of our variable created in the .data section. RDI will be loaded with the file we want to write to – in this case STDOUT. The datatype and meaning of the arguments passed can be found in the function’s definition. We compile, link and run the program using the commands below.

Hello World Code

; Hello World Program - 64-bit

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 helloworld.asm

; Link with : ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld.o -o helloworld

; Run with: ./helloworld

SECTION .data

msg db 'Hello World!', 0Ah ; assign msg variable with your message string

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rdx, 13 ; number of bytes to write - one for each letter plus 0Ah (line feed character)

mov rsi, msg ; move the memory address of our message string into ecx

mov rdi, 1 ; write to the STDOUT file

mov rax, 1 ; invoke SYS_WRITE (kernel opcode 1)

syscall

~$ nasm -f elf64 helloworld.asm

~$ ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld.o -o helloworld

~$ ./helloworld

Hello World!

Segmentation fault

Lesson 2

Proper program exit

Some more background

After successfully learning how to execute a system call in Lesson 1 we now need to learn about one of the most important system calls in the kernel, sys_exit.

Notice how after our ‘Hello, world!’ program ran we got a Segmentation fault? Well, computer programs can be thought of as a long strip of instructions that are loaded into memory and divided up into sections (or segments). This general pool of memory is shared between all programs and can be used to store variables, instructions, other programs or anything really. Each segment is given an address so that information stored in that section can be found later.

To execute a program that is loaded in memory, we use the global label _start: to tell the operating system where in memory our program can be found and executed. Memory is then accessed sequentially following the program logic which determines the next address to be accessed. The kernel jumps to that address in memory and executes it.

It’s important to tell the operating system exactly where it should begin execution and where it should stop. In Lesson 1 we didn’t tell the kernel where to stop execution. So, after we called sys_write the program continued sequentially executing the next address in memory, which could have been anything. We don’t know what the kernel tried to execute but it caused it to choke and terminate the process for us instead - leaving us the error message of ‘Segmentation fault’. Calling sys_exit at the end of all our programs will mean the kernel knows exactly when to terminate the process and return memory back to the general pool thus avoiding an error.

Writing our program sys_exit has a simple function definition. In the Linux System Call Table it is allocated OPCODE 60 and is passed a single argument through RDI.

In order to execute this function all we need to do is:

Load RDI with 0 to pass zero to the function meaning ‘zero errors’. Load RAX with 60 to call sys_exit. Then request an interrupt on libc using syscall. We then compile, link and run it again.

Note: Only new code added in each lesson will be commented.

; Hello World Program - asmtutor.com

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 helloworld.asm

; Link with : ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld.o -o helloworld

; Run with: ./helloworld

SECTION .data

msg db 'Hello World!', 0Ah

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rdx, 13

mov rsi, msg

mov rdi, 1

mov rax, 1

syscall

mov rdi, 0 ; return 0 status on exit - 'No Errors'

mov rax, 60 ; invoke SYS_EXIT (kernel opcode 60)

syscall

~$ nasm -f elf64 helloworld.asm

~$ ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld.o -o helloworld

~$ ./helloworld

Hello World!

Lesson 3

Calculate string length

Firstly, some background

Why do we need to calculate the length of a string?

Well sys_write requires that we pass it a pointer to the string we want to output in memory and the length in bytes we want to print out. If we were to modify our message string we would have to update the length in bytes that we pass to sys_write as well, otherwise it will not print correctly.

You can see what I mean using the program in Lesson 2. Modify the message string to say ‘Hello, brave new world!’ then compile, link and run the new program. The output will be ‘Hello, brave ‘ (the first 13 characters) because we are still only passing 13 bytes to sys_write as its length. It will be particularly necessary when we want to print out user input. As we won’t know the length of the data when we compile our program, we will need a way to calculate the length at runtime in order to successfully print it out.

Writing our program

To calculate the length of the string we will use a technique called pointer arithmetic. Two registers are initialised pointing to the same address in memory. One register (in this case RAX) will be incremented forward one byte for each character in the output string until we reach the end of the string. The original pointer will then be subtracted from RAX. This is effectively like subtraction between two arrays and the result yields the number of elements between the two addresses. This result is then passed to sys_write replacing our hard coded count.

The CMP instruction compares the left hand side against the right hand side and sets a number of flags that are used for program flow. The flag we’re checking is the ZF or Zero Flag. When the byte that RAX points to is equal to zero the ZF flag is set. We then use the JZ instruction to jump, if the ZF flag is set, to the point in our program labeled ‘finished’. This is to break out of the nextchar loop and continue executing the rest of the program.

; Hello World Program (Calculating string length)

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 helloworld-len64.asm

; Link with : ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-len64.o -o helloworld-len64

; Run with: ./helloworld-len

SECTION .data

msg db 'Hello, brave new world!', 0Ah ; we can modify this now without having to update anywhere else in the program

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rdi, msg ; move the address of our message string into RDI

mov rax, rdi ; move the address in RDI into RAX as well (Both now point to the same segment in memory)

nextchar:

cmp byte [rax], 0 ; compare the byte pointed to by RAX at this address against zero (Zero is an end of string delimiter)

jz finished ; jump (if the zero flagged has been set) to the point in the code labeled 'finished'

inc rax ; increment the address in RAX by one byte (if the zero flagged has NOT been set)

jmp nextchar ; jump to the point in the code labeled 'nextchar'

finished:

sub rax, rdi ; subtract the address in RDI from the address in RAX

; remember both registers started pointing to the same address (see line 15)

; but RAX has been incremented one byte for each character in the message string

; when you subtract one memory address from another of the same type

; the result is number of segments between them - in this case the number of bytes

mov rdx, rax ; RAX now equals the number of bytes in our string

mov rsi, msg ; the rest of the code should be familiar now

mov rdi, 1

mov rax, 1

syscall

mov rdi, 0

mov rax, 60

syscall

nasm -f elf64 helloworld-len64.asm

ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-len64.o -o helloworld-len64

./helloworld-len64

Hello, brave new world!

Lesson 4

Subroutines

Introduction to subroutines

Subroutines are functions. They are reusable pieces of code that can be called by your program to perform various repeatable tasks. Subroutines are declared using labels just like we’ve used before (eg. _start:) however we don’t use the JMP instruction to get to them - instead we use a new instruction CALL. We also don’t use the JMP instruction to return to our program after we have run the function. To return to our program from a subroutine we use the instruction RET instead. Why don’t we JMP to subroutines?

The great thing about writing a subroutine is that we can reuse it. If we want to be able to use the subroutine from anywhere in the code we would have to write some logic to determine where in the code we had jumped from and where we should jump back to. This would litter our code with unwanted labels. If we use CALL and RET however, assembly handles this problem for us using something called the stack. Introduction to the stack

The stack is a special type of memory. It’s the same type of memory that we’ve used before however it’s special in how it is used by our program. The stack is what is call Last In First Out memory (LIFO). You can think of the stack like a stack of plates in your kitchen. The last plate you put on the stack is also the first plate you will take off the stack next time you use a plate.

The stack in assembly is not storing plates though, its storing values. You can store a lot of things on the stack such as variables, addresses or other programs. We need to use the stack when we call subroutines to temporarily store values that will be restored later.

Any register that your function needs to use should have it’s current value put on the stack for safe keeping using the PUSH instruction. Then after the function has finished it’s logic, these registers can have their original values restored using the POP instruction. This means that any values in the registers will be the same before and after you’ve called your function. If we take care of this in our subroutine we can call functions without worrying about what changes they’re making to our registers.

The CALL and RET instructions also use the stack. When you CALL a subroutine, the address you called it from in your program is pushed onto the stack. This address is then popped off the stack by RET and the program jumps back to that place in your code. This is why you should always JMP to labels but you should CALL functions.

; Hello World Program (Subroutines)

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 helloworld-len64.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-len64.o -o helloworld-len64

; Run with: ./helloworld-len64

SECTION .data

msg db 'Hello, brave new world!', 0Ah

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rax, msg ; move the address of our message string into RAX

call strlen ; call our function to calculate the length of the string

mov rdx, rax ; our function leaves the result in RAX

mov rsi, msg ; this is all the same as before

mov rdi, 1

mov rax, 1

syscall

mov rdi, 0

mov rax, 60

syscall

strlen: ; this is our first function declaration

push rdi ; push the value in RDI onto the stack to preserve it while we use RDI in this function

mov rdi, rax ; move the address in RAX into RDI (Both point to the same segment in memory)

nextchar: ; this is the same as lesson3

cmp byte [rax], 0

jz finished

inc rax

jmp nextchar

finished:

sub rax, rdi

pop rdi ; pop the value on the stack back into RAX

ret ; return to where the function was called

nasm -f elf64 helloworld-len64.asm

ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-len64.o -o helloworld-len64

./helloworld-len64

Hello, brave new world!

Lesson 5

External include files

External include files allow us to move code from our program and put it into separate files. This technique is useful for writing clean, easy to maintain programs. Reusable bits of code can be written as subroutines and stored in separate files called libraries. When you need a piece of logic you can include the file in your program and use it as if they are part of the same file.

In this lesson we will move our string length calculating subroutine into an external file. We fill also make our string printing logic and program exit logic a subroutine and we will move them into this external file. Once it’s completed our actual program will be clean and easier to read.

We can then declare another message variable and call our print function twice in order to demonstrate how we can reuse code.

Note: I won’t be showing the code in functions.asm after this lesson unless it changes. It will just be included if needed.

functions.asm

;------------------------------------------

; int slen(String message)

; String length calculation function

slen:

push rdi

mov rdi, rax

nextchar:

cmp byte [rax], 0

jz finished

inc rax

jmp nextchar

finished:

sub rax, rdi

pop rdi

ret

;------------------------------------------

; void sprint(String message)

; String printing function

sprint:

push rdx

push rsi

push rdi

push rax

call slen

mov rdx, rax

pop rax

mov rsi, rax

mov rdi, 1

mov rax, 1

syscall

pop rdi

pop rsi

pop rdx

ret

;------------------------------------------

; void exit()

; Exit program and restore resources

quit:

mov rdi, 0

mov rax, 60

syscall

ret

helloworld-inc64.asm

; Hello World Program (External file include)

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 helloworld-inc64.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-inc64.o -o helloworld-inc64

; Run with: ./helloworld-inc64

%include 'functions.asm' ; include our external file

SECTION .data

msg1 db 'Hello, brave new world!', 0Ah ; our first message string

msg2 db 'This is how we recycle in NASM.', 0Ah ; our second message string

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rax, msg1 ; move the address of our first message string into RAX

call sprint ; call our string printing function

mov rax, msg2 ; move the address of our second message string into RAX

call sprint ; call our string printing function

call quit ; call our quit function

nasm -f elf64 helloworld-inc64.asm

ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-inc64.o -o helloworld-inc64

./helloworld-inc64

Hello, brave new world!

This is how we recycle in NASM.

This is how we recycle in NASM.

Error: Our second message is outputted twice. This is fixed in the next lesson.

Lesson 6

NULL terminating bytes Ok so why did our second message print twice when we only called our sprint function on msg2 once? Well actually it did only print once. You can see what I mean if you comment out our second call to sprint. The output will be both of our message strings.

But how is this possible?

What is happening is we weren’t properly terminating our strings. In assembly, variables are stored one after another in memory so the last byte of our msg1 variable is right next to the first byte of our msg2 variable. We know our string length calculation is looking for a zero byte so unless our msg2 variable starts with a zero byte it keeps counting as if it’s the same string (and as far as assembly is concerned it is the same string). So we need to put a zero byte or 0h after our strings to let assembly know where to stop counting.

Note: In programming 0h denotes a null byte and a null byte after a string tells assembly where it ends in memory.

; Hello World Program (External file include)

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 helloworld-inc64.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-inc64.o -o helloworld-inc64

; Run with: ./helloworld-inc64

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .data

msg1 db 'Hello, brave new world!', 0Ah, 0h ; NOTE the null terminating byte

msg2 db 'This is how we recycle in NASM.', 0Ah, 0h ; NOTE the null terminating byte

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rax, msg1

call sprint

mov rax, msg2

call sprint

call quit

~$ nasm -f elf64 helloworld-inc64.asm

~$ ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-inc64.o -o helloworld-inc64

~$ ./helloworld-inc64

Hello, brave new world!

This is how we recycle in NASM.

Lesson 7

Linefeeds

Linefeeds are essential to console programs like our ‘hello world’ program. They become even more important once we start building programs that require user input. But linefeeds can be a pain to maintain. Sometimes you will want to include them in your strings and sometimes you will want to remove them. If we continue to hard code them in our variables by adding 0Ah after our declared message text, it will become a problem. If there’s a place in the code that we don’t want to print out the linefeed for that variable we will need to write some extra logic remove it from the string at runtime.

It would be better for the maintainability of our program if we write a subroutine that will print out our message and then print a linefeed afterwards. That way we can just call this subroutine when we need the linefeed and call our current sprint subroutine when we don’t.

A call to sys_write requires we pass a pointer to an address in memory of the string we want to print so we can’t just pass a linefeed character (0Ah) to our print function. We also don’t want to create another variable just to hold a linefeed character so we will instead use the stack.

The way it works is by moving a linefeed character into RAX. We then push RAX onto the stack and get the address pointed to by the Extended Stack Pointer. RSP is another register. When you push items onto the stack, RSP is decremented to point to the address in memory of the last item and so it can be used to access that item directly from the stack. Since RSP points to an address in memory of a character, sys_write will be able to use it to print.

functions.asm

;------------------------------------------

; int slen(String message)

; String length calculation function

slen:

push rdi

mov rdi, rax

nextchar:

cmp byte [rax], 0

jz finished

inc rax

jmp nextchar

finished:

sub rax, rdi

pop rdi

ret

;------------------------------------------

; void sprint(String message)

; String printing function

sprint:

push rdx

push rsi

push rdi

push rax

call slen

mov rdx, rax

pop rax

mov rsi, rax

mov rdi, 1

mov rax, 1

syscall

pop rdi

pop rsi

pop rdx

ret

;------------------------------------------

; void sprintLF(String message)

; String printing with line feed function

sprintLF:

call sprint

push rax ; push eax onto the stack to preserve it while we use the eax register in this function

mov rax, 0Ah ; move 0Ah into eax - 0Ah is the ascii character for a linefeed

push rax ; push the linefeed onto the stack so we can get the address

mov rax, rsp ; move the address of the current stack pointer into eax for sprint

call sprint ; call our sprint function

pop rax ; remove our linefeed character from the stack

pop rax ; restore the original value of eax before our function was called

ret ; return to our program

;------------------------------------------

; void exit()

; Exit program and restore resources

quit:

mov rdi, 0

mov rax, 60

syscall

ret

helloworld-lf.asm

; Hello World Program (External file include)

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 helloworld-lf.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-lf.o -o helloworld-lf

; Run with: ./helloworld-inc64

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .data

msg1 db 'Hello, brave new world!', 0h ; NOTE we have removed the line feed character 0Ah

msg2 db 'This is how we recycle in NASM.', 0h ; NOTE we have removed the line feed character 0Ah

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rax, msg1

call sprintLF ; NOTE we are calling our new print with linefeed function

mov rax, msg2

call sprintLF ; NOTE we are calling our new print with linefeed function

call quit

nasm -f elf64 helloworld-lf.asm

ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-lf.o -o helloworld-lf

./helloworld-lf

Hello, brave new world!

This is how we recycle in NASM.

Lesson 8

Passing arguments

In x86 we used to be able to use ECX register as our counter for the loop. Although it’s a general-purpose register it’s original intention was to be used as a counter. Passing arguments to your program from the command line is as easy as popping them off the stack in NASM. When we run our program in x86, any passed arguments are loaded onto the stack in reverse order. The name of the program is then loaded onto the stack and lastly the total number of arguments is loaded onto the stack. The last two stack items for a NASM compiled program are always the name of the program and the number of passed arguments.

So in x86 all we have to do to use them is pop the number of arguments off the stack first, then iterate once for each argument and perform our logic. In our program that means calling our print function.

helloworld-args.asm

; Hello World Program (Passing arguments from the command line)

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 helloworld-args.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-args.o -o helloworld-args

; Run with: ./helloworld-args

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

pop rcx ; first value on the stack is the number of arguments

nextArg:

cmp rcx, 0h ; check to see if we have any arguments left

jz noMoreArgs ; if zero flag is set jump to noMoreArgs label (jumping over the end of the loop)

pop rax ; pop the next argument off the stack

call sprintLF ; call our print with linefeed function

dec rcx ; decrease rcx (number of arguments left) by 1

jmp nextArg ; jump to nextArg label

noMoreArgs:

call quit

~$ nasm -f elf64 helloworld-args.asm

~$ ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-args.o -o helloworld-args

~$ ./helloworld-args "This is one argument" "This is another" 101

./helloworld-args

This is one argument

This is another 101

Error Segmentation Fault

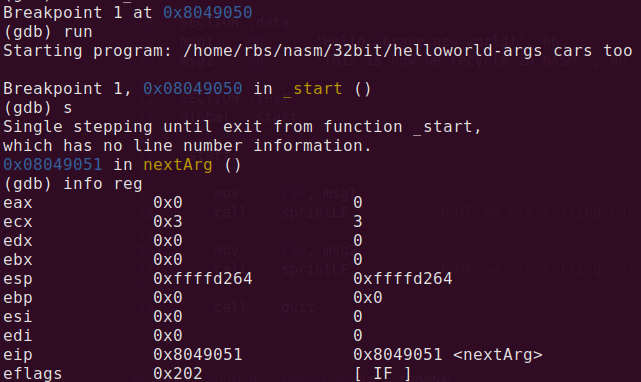

If we were to compile the x86 version from Lesson 8 tutorial in asmtutor.com using the nasm -g option we could see the counter gets decremented correctly in GDB. As shown below we start with 3 in ECX. After continously clicking s to step in or n for next in Gdb eventually the program will exit. With ECX showing zero and no segmentation fault.

nasm -g -f elf helloworld-args.asm

ld -m elf_i386 helloworld-args.o -o helloworld-args

gdb --args ./helloworld-args "cars" "too"

break _start

run

s

info registers

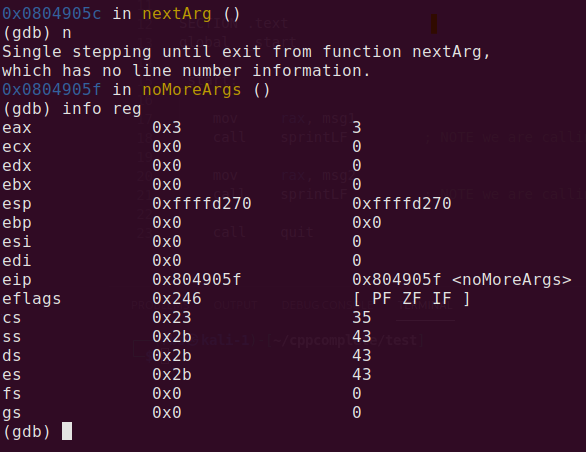

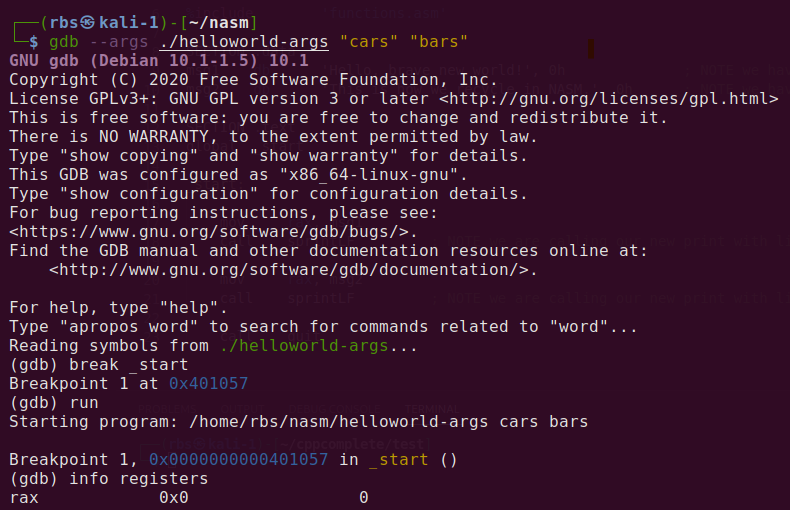

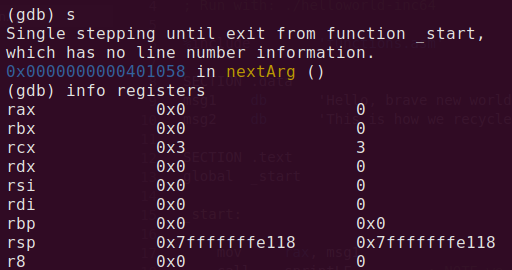

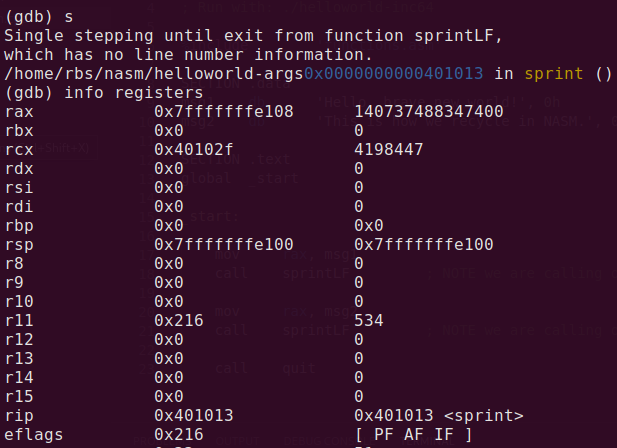

Now if we go back to our 64-bit example and compile it with nasm -g option for debugging we get a segmentation fault. We can see that at first we have 3 in ecx. Our program even prints out the correct stuff. This is due to helloworld-args saving the rcx through pop rcx. However once we get into sprint our code uses a syscall which clobbers the rcx value with a random value. d

nasm -g -f elf64 helloworld-args.asm

ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-args.o -o helloworld-args

gdb --args ./helloworld-args "cars" "too"

break _start

run

n

info registers

Now that rcx has been clobbered the code will run even printing the right arguments. However the code will return back and never hit jz noMoreArgs The reason being that it will think there are still more arguments left. eventually hitting a segmentation fault while in our functions.asm. Click here to learn more about syscall clobber What we know need to do is find a way to print the arguments without relying on RCX.

nasm -g -f elf64 helloworld-args.asm

ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-args.o -o helloworld-args

gdb --args ./helloworld-args "cars" "too"

Lesson 8-1

Passing arguments 64-bit style

Seeing that RCX won’t work like we could do in x86 using ECX. We need to use a different technique to print out arguments. Since we start without calling syscall we still have RCX holding the amount of arguments. So what we can do is move RCX into a placeholder and clear it when done using it. In this case I have updated the code to use r8. we move RCX in R8 and can now forget about RCX which will get clobbered by SYSCALL (SYSCALL also clobbers r11 register). Keep in mind if r8 was going to be used by other areas of your code you can run into issues. As we can see below it works succesfully.

This example shows another way we can do this in 64-bit

helloworld-args.asm

; Hello World Program (Passing arguments from the command line)

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 helloworld-args.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-args.o -o helloworld-args

; Run with: ./helloworld-args

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

pop rcx ; first value on the stack is the number of arguments

mov r8,rcx ; Since rcx gets clobbered lets move it into r8

nextArg:

cmp r8, 0h ; check to see if we have any arguments left

jz noMoreArgs ; if zero flag is set jump to noMoreArgs label (jumping over the end of the loop)

pop rax ; pop the next argument off the stack

call sprintLF ; call our print with linefeed function

dec r8 ; decrease rcx (number of arguments left) by 1

jmp nextArg ; jump to nextArg label

noMoreArgs:

call quit

~$ nasm -f elf64 helloworld-args.asm

~$ ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-args.o -o helloworld-args

~$ ./helloworld-args "This is one argument" "This is another" 101

./helloworld-args

This is one argument

This is another

101

lesson-9

User input

Introduction to the .bss section

So far we’ve used the .text and .data section so now it’s time to introduce the .bss section. BSS stands for Block Started by Symbol. It is an area in our program that is used to reserve space in memory for uninitialised variables. We will use it to reserve some space in memory to hold our user input since we don’t know how many bytes we’ll need to store.

The syntax to declare variables is as follows: .bss section example

SECTION .bss

variableName1: RESB 1 ; reserve space for 1 byte

variableName2: RESW 1 ; reserve space for 1 word

variableName3: RESD 1 ; reserve space for 1 double word

variableName4: RESQ 1 ; reserve space for 1 double precision float (quad word)

variableName5: REST 1 ; reserve space for 1 extended precision float

Writing our program

We will be using the system call sys_read to receive and process input from the user. This function is assigned OPCODE 0 in the Linux System Call Table. Just like sys_write this function also takes 3 arguments which will be loaded into RDX, RSI and RDI before requesting a software interrupt that will call the function.

The arguments passed are as follows:

- RDX will be loaded with the maximum length (in bytes) of the space in memory.

- RSI will be loaded with the address of our variable created in the .bss section.

- RDI will be loaded with the file we want to write to – in this case STDIN.

As always the datatype and meaning of the arguments passed can be found in the function’s definition.

When sys_read detects a linefeed, control returns to the program and the users input is located at the memory address you passed in RSI.

helloworld-input.asm

; Hello World Program (Getting input)

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 helloworld-input.asm

; Link with ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-input.o -o helloworld-input

; Run with: ./helloworld-input

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .data

msg1 db 'Please enter your name: ', 0h ; message string asking user for input

msg2 db 'Hello, ', 0h ; message string to use after user has entered their name

SECTION .bss

sinput: resb 255 ; reserve a 255 byte space in memory for the users input string

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rax, msg1

call sprint

mov rdx, 255 ; number of bytes to read

mov rsi, sinput ; reserved space to store our input (known as a buffer)

mov rdi, 0 ; write to the STDIN file

mov rax, 0 ; invoke SYS_READ (kernel opcode 0)

syscall

mov rax, msg2

call sprint

mov rax, sinput ; move our buffer into eax (Note: input contains a linefeed)

call sprint ; call our print function

call quit

lesson-10

Count to 10

Firstly, some background

Counting by numbers is not as straight forward as you would think in assembly. Firstly we need to pass sys_write an address in memory so we can’t just load our register with a number and call our print function. Secondly, numbers and strings are very different things in assembly. Strings are represented by what are called ASCII values. ASCII stands for American Standard Code for Information Interchange. A good reference for ASCII can be found here. ASCII was created as a way to standardise the representation of strings across all computers.

Remember, we can’t print a number - we have to print a string. In order to count to 10 we will need to convert our numbers from standard integers to their ASCII string representations. Have a look at the ASCII values table and notice that the string representation for the number ‘1’ is actually ‘49’ in ASCII. In fact, adding 48 to our numbers is all we have to do to convert them from integers to their ASCII string representations. Writing our program

What we will do with our program is count from 1 to 10 using the R8 register. We will then add 48 to our counter to convert it from a number to it’s ASCII string representation. We will then push this value to the stack and call our print function passing RSP as the memory address to print from. Once we have finished counting to 10 we will exit our counting loop and call our quit function.

helloworld-10.asm

; Hello World Program (Count to 10)

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 helloworld-10.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-10.o -o helloworld-10

; Run with: ./helloworld-10

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov r8, 0 ; r8 is initalised to zero.

nextNumber:

inc r8 ; increment r8

mov rax, r8 ; move the address of our integer into rax

add rax, 48 ; add 48 to our number to convert from integer to ascii for printing

push rax ; push rax to the stack

mov rax, rsp ; get the address of the character on the stack

call sprintLF ; call our print function

pop rax ; clean up the stack so we don't have unneeded bytes taking up space

cmp r8, 10 ; have we reached 10 yet? compare our counter with decimal 10

jne nextNumber ; jump if not equal and keep counting

call quit

~$ nasm -f elf helloworld-10.asm

~$ ld -m elf_i386 helloworld-10.o -o helloworld-10

~$ ./helloworld-10

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

:

Error: Our number 10 prints a colon (:) character instead. What’s going on?

lesson-11

Count to 10 (itoa)

So why did our program in Lesson 10 print out a colon character instead of the number 10?. Well lets have a look at our ASCII table. We can see that the colon character has a ASCII value of 58. We were adding 48 to our integers to convert them to their ASCII string representations so instead of passing sys_write the value ‘58’ to print ten we actually need to pass the ASCII value for the number 1 followed by the ASCII value for the number 0. Passing sys_write ‘4948’ is the correct string representation for the number ‘10’. So we can’t just simply add 48 to our numbers to convert them, we first have to divide them by 10 because each place value needs to be converted individually.

We will write 2 new subroutines in this lesson ‘iprint’ and ‘iprintLF’. These functions will be used when we want to print ASCII string representations of numbers. We achieve this by passing the number in RAX. We then initialise a counter in R8. We will repeatedly divide the number by 10 and each time convert the remainder to a string by adding 48. We will then push this onto the stack for later use. Once we can no longer divide the number by 10 we will enter our second loop. In this print loop we will print the now converted string representations from the stack and pop them off. Popping them off the stack moves RSP forward to the next item on the stack. Each time we print a value we will decrease our counter R8. Once all numbers have been converted and printed we will return to our program.

How does the divide instruction work?

The DIV and IDIV instructions work by dividing whatever is in RAX by the value passed to the instruction. The quotient part of the value is left in RAX and the remainder part is put into RDX (Originally called the data register).

For example. IDIV instruction example

mov rax, 10 ; move 10 into rax

mov rsi, 10 ; move 10 into rsi

idiv rsi ; divide rax by rsi (rax will equal 1 and rdx will equal 0)

idiv rsi ; divide rax by rsi again (rax will equal 0 and rdx will equal 1)

If we are only storing the remainder won’t we have problems?

No, because these are integers, when you divide a number by an even bigger number the quotient in RAX is 0 and the remainder is the number itself. This is because the number divides zero times leaving the original value as the remainder in RDX. How good is that?

Note: Only the new functions iprint and iprintLF have comments.

functions.asm

;------------------------------------------

; void iprint(Integer number)

; Integer printing function (itoa)

iprint:

push rax ; preserve rax on the stack to be restored after function runs

push r8 ; preserve r8 on the stack to be restored after function runs

push rdx ; preserve rdx on the stack to be restored after function runs

push rsi ; preserve rsi on the stack to be restored after function runs

mov r8, 0 ; counter of how many bytes we need to print in the end

divideLoop:

inc r8 ; count each byte to print - number of characters

mov rdx, 0 ; empty rdx

mov rsi, 10 ; mov 10 into rsi

idiv rsi ; divide rax by rsi

add rdx, 48 ; convert rdx to it's ascii representation - rdx holds the remainder after a divide instruction

push rdx ; push rdx (string representation of an intger) onto the stack

cmp rax, 0 ; can the integer be divided anymore?

jnz divideLoop ; jump if not zero to the label divideLoop

printLoop:

dec r8 ; count down each byte that we put on the stack

mov rax, rsp ; mov the stack pointer into rax for printing

call sprint ; call our string print function

pop rax ; remove last character from the stack to move esp forward

cmp r8, 0 ; have we printed all bytes we pushed onto the stack?

jnz printLoop ; jump is not zero to the label printLoop

pop rsi ; restore rsi from the value we pushed onto the stack at the start

pop rdx ; restore rdx from the value we pushed onto the stack at the start

pop r8 ; restore r8 from the value we pushed onto the stack at the start

pop rax ; restore rax from the value we pushed onto the stack at the start

ret

;------------------------------------------

; void iprintLF(Integer number)

; Integer printing function with linefeed (itoa)

iprintLF:

call iprint ; call our integer printing function

push rax ; push rax onto the stack to preserve it while we use the rax register in this function

mov rax, 0Ah ; move 0Ah into rax - 0Ah is the ascii character for a linefeed

push rax ; push the linefeed onto the stack so we can get the address

mov rax, esp ; move the address of the current stack pointer into rax for sprint

call sprint ; call our sprint function

pop rax ; remove our linefeed character from the stack

pop rax ; restore the original value of rax before our function was called

ret

;------------------------------------------

; int slen(String message)

; String length calculation function

slen:

push rdi

mov rdi, rax

nextchar:

cmp byte [rax], 0

jz finished

inc rax

jmp nextchar

finished:

sub rax, rdi

pop rdi

ret

;------------------------------------------

; void sprint(String message)

; String printing function

sprint:

push rdx

push rsi

push rdi

push rax

call slen

mov rdx, rax

pop rax

mov rsi, rax

mov rdi, 1

mov rax, 1

syscall

pop rdi

pop rsi

pop rdx

ret

;------------------------------------------

; void sprintLF(String message)

; String printing with line feed function

sprintLF:

call sprint

push rax

mov rax, 0Ah

push rax

mov rax, rsp

call sprint

pop rax

pop rax

ret

;------------------------------------------

; void exit()

; Exit program and restore resources

quit:

mov rdi, 0

mov rax, 60

syscall

ret

helloworld-itoa.asm

; Hello World Program (Count to 10 itoa)

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 helloworld-itoa.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 helloworld-itoa.o -o helloworld-itoa

; Run with: ./helloworld-itoa

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov r8, 0

nextNumber:

inc r8

mov rax, r8

call iprintLF ; NOTE call our new integer printing function (itoa)

cmp r8, 10

jne nextNumber

call quit

It should now print 1-10 correctly after compile and link

lesson-12

Calculator - addition

In this program we will be adding the registers RAX and RBX together and we’ll leave our answer in RAX. Firstly we use the MOV instruction to load RAX with an integer (in this case 90). We then MOV an integer into RBX (in this case 9). Now all we need to do is use the ADD instruction to perform our addition. RBX & RAX will be added together leaving our answer in the left most register in this instruction (in our case RAX). Then all we need to do is call our integer printing function to complete the program. calculator-addition.asm

; Calculator (Addition)

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 calculator-addition.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 calculator-addition.o -o calculator-addition

; Run with: ./calculator-addition

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rax, 90 ; move our first number into rax

mov rbx, 9 ; move our second number into rbx

add rax, rbx ; add rbx to rax

call iprintLF ; call our integer print with linefeed function

call quit

After link and compile running it should print out 99 $ ./calculator-addition 99

lesson-13

Calculator - subtraction In this program we will be subtracting the value in the register RBX from the value in the register RAX. Firstly we load RAX and RBX with integers in the same way as Lesson 12. The only difference is we will be using the SUB instruction to perform our subtraction logic, leaving our answer in the left most register of this instruction (in our case RAX). Then all we need to do is call our integer printing function to complete the program. calculator-subtraction.asm

; Calculator (Subtraction)

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 calculator-subtraction.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 calculator-subtraction.o -o calculator-subtraction

; Run with: ./calculator-subtraction

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rax, 90 ; move our first number into rax

mov rbx, 9 ; move our second number into rbx

sub rax, rbx ; subtract rbx from rax

call iprintLF ; call our integer print with linefeed function

call quit

lesson-14

Calculator - multiplication In this program we will be multiplying the value in RBX by the value present in RAX. Firstly we load RAX and RBX with integers in the same way as Lesson 12. This time though we will be calling the MUL instruction to perform our multiplication logic. The MUL instruction is different from many instructions in NASM, in that it only accepts one further argument. The MUL instruction always multiples RAX by whatever value is passed after it. The answer is left in RAX.

calculator-multiplication.asm

; Calculator (Multiplication)

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 calculator-multiplication.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 calculator-multiplication.o -o calculator-multiplication

; Run with: ./calculator-multiplication

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rax, 90 ; move our first number into rax

mov rbx, 9 ; move our second number into rbx

mul rbx ; multiply rax by rbx

call iprintLF ; call our integer print with linefeed function

call quit

lesson-15

###Calculator - division

In this program we will be dividing the value in RBX by the value present in RAX. We’ve used division before in our integer print subroutine. Our program requires a few extra strings in order to print out the correct answer but otherwise there’s nothing complicated going on.

Firstly we load RAX and RBX with integers in the same way as Lesson 12. Division logic is performed using the DIV instruction. The DIV instruction always divides RAX by the value passed after it. It will leave the quotient part of the answer in RAX and put the remainder part in RDX (the original data register). We then MOV and call our strings and integers to print out the correct answer.

calculator-division.asm

; Calculator (Division)

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 calculator-division.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 calculator-division.o -o calculator-division

; Run with: ./calculator-division

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .data

msg1 db ' remainder ' ; a message string to correctly output result

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rax, 90 ; move our first number into rax

mov rbx, 9 ; move our second number into rbx

div rbx ; divide rax by rbx

call iprint ; call our integer print function on the quotient

mov rax, msg1 ; move our message string into rax

call sprint ; call our string print function

mov rax, rdx ; move our remainder into rax

call iprintLF ; call our integer printing with linefeed function

call quit

lesson-16

Calculator (atoi) Our program will take several command line arguments and add them together printing out the result in the terminal.

Writing our program

Our program begins by using the POP instruction to get the number of passed arguments off the stack. This value is stored in RCX (originally known as the counter register). It will then POP the next value off the stack containing the program name and remove it from the number of arguments stored in RCX. It will then loop through the rest of the arguments popping each one off the stack and performing our addition logic. As we know, arguments passed via the command line are received by our program as strings. Before we can add the arguments together we will need to convert them to integers otherwise our result will not be correct. We do this by calling our Ascii to Integer function (atoi). This function will convert the ascii value into an integer and place the result in RAX. We can then add this value to EDX (originally known as the data register) where we will store the result of our additions. If the value passed to atoi is not an ascii representation of an integer our function will return zero instead. When all arguments have been converted and added together we will print out the result and call our quit function.

How does the atoi function work

Converting an ascii string into an integer value is not a trivial task. We know how to convert an integer to an ascii string so the process should essentially work in reverse. Firstly we take the address of the string and move it into RSI (originally known as the source register). We will then move along the string byte by byte (think of each byte as being a single digit or decimal placeholder). For each digit we will check if it’s value is between 48-57 (ascii values for the digits 0-9).

Once we have performed this check and determined that the byte can be converted to an integer we will perform the following logic. We will subtract 48 from the value – converting the ascii value to it’s decimal equivalent. We will then add this value to RAX (the general purpose register that will store our result). We will then multiple RAX by 10 as each byte represents a decimal placeholder and continue the loop.

When all bytes have been converted we need to do one last thing before we return the result. The last digit of any number represents a single unit (not a multiple of 10) so we have multiplied our result one too many times. We simple divide it by 10 once to correct this and then return. If no integer arguments were pass however, we skip this divide instruction.

What is the BL register

You may have noticed that the atoi function references the BL register. So far in these tutorials we have been exclusively using 32bit registers. These 32bit general purpose registers contain segments of memory that can also be referenced. These segments are available in 16bits and 8bits. We wanted a single byte (8bits) because a byte is the size of memory that is required to store a single ascii character. If we used a larger memory size we would have copied 8bits of data into 32bits of space leaving us with ‘rubbish’ bits - because only the first 8bits would be meaningful for our calculation.

The RBX register is 32bits. RBX’s 16 bit segment is referenced as BX. BX contains the 8bit segments BL and BH (Lower and Higher bits). We wanted the first 8bits (lower bits) of RBX and so we referenced that storage area using BL.

Almost every assembly language tutorial begins with a history of the registers, their names and their sizes. These tutorials however were written to provide a foundation in NASM by first writing code and then understanding the theory. The full story about the size of registers, their history and importance are beyond the scope of this tutorial but we will return to that story in later tutorials.

Note: Only the new function in this file ‘atoi’ is shown below. Also functions.asm does have RCX changed to R8 register since 64-bit clobbers RCX in syscalls. However the main calculator-atoi.asm doesn’t use syscall until the end when it calls iprintLF, which eventually calls a syscall in functions.asm. This is why I changed ECX to RCX and left it at that, since we would have already pulled our arguments off the stack, and it won’t matter anymore that RCX gets clobbered.

functions.asm

;------------------------------------------

; int atoi(Integer number)

; Ascii to integer function (atoi)

atoi:

push rbx ; preserve rbx on the stack to be restored after function runs

push r8 ; preserve r8 on the stack to be restored after function runs

push rdx ; preserve rdx on the stack to be restored after function runs

push rsi ; preserve rsi on the stack to be restored after function runs

mov rsi, rax ; move pointer in rax into rsi (our number to convert)

mov rax, 0 ; initialise rax with decimal value 0

mov r8, 0 ; initialise r8 with decimal value 0

.multiplyLoop:

xor rbx, rbx ; resets both lower and uppper bytes of rbx to be 0

mov bl, [rsi+r8] ; move a single byte into rbx register's lower half

cmp bl, 48 ; compare rbx register's lower half value against ascii value 48 (char value 0)

jl .finished ; jump if less than to label finished

cmp bl, 57 ; compare rbx register's lower half value against ascii value 57 (char value 9)

jg .finished ; jump if greater than to label finished

sub bl, 48 ; convert rbx register's lower half to decimal representation of ascii value

add rax, rbx ; add rbx to our interger value in rax

mov rbx, 10 ; move decimal value 10 into rbx

mul rbx ; multiply rax by rbx to get place value

inc r8 ; increment r8 (our counter register)

jmp .multiplyLoop ; continue multiply loop

.finished:

cmp r8, 0 ; compare r8 register's value against decimal 0 (our counter register)

je .restore ; jump if equal to 0 (no integer arguments were passed to atoi)

mov rbx, 10 ; move decimal value 10 into rbx

div rbx ; divide rax by value in rbx (in this case 10)

.restore:

pop rsi ; restore rsi from the value we pushed onto the stack at the start

pop rdx ; restore rdx from the value we pushed onto the stack at the start

pop r8 ; restore r8 from the value we pushed onto the stack at the start

pop rbx ; restore rbx from the value we pushed onto the stack at the start

ret

calculator-atoi.asm

; Calculator (ATOI)

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 calculator-atoi.asm

;; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 calculator-atoi.o -o calculator-atoi

; Run with: ./calculator-atoi 20 1000 317

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

pop rcx ; first value on the stack is the number of arguments

pop rdx ; second value on the stack is the program name (discarded when we initialise rdx)

sub rcx, 1 ; decrease rcx by 1 (number of arguments without program name)

mov rdx, 0 ; initialise our data register to store additions

nextArg:

cmp rcx, 0h ; check to see if we have any arguments left

jz noMoreArgs ; if zero flag is set jump to noMoreArgs label (jumping over the end of the loop)

pop rax ; pop the next argument off the stack

call atoi ; convert our ascii string to decimal integer

add rdx, rax ; perform our addition logic

dec rcx ; decrease rcx (number of arguments left) by 1

jmp nextArg ; jump to nextArg label

noMoreArgs:

mov rax, rdx ; move our data result into rax for printing

call iprintLF ; call our integer printing with linefeed function

call quit ; call our quit function

~$ nasm -f elf64 calculator-atoi.asm

~$ ld -m elf_x86_64 calculator-atoi.o -o calculator-atoi

~$ ./calculator-atoi 20 1000 317

1337

lesson-17

###Namespace

Namespace is a necessary construct in any software project that involves a codebase that is larger than a few simple functions. Namespace provides scope to your identifiers and allows you to reuse naming conventions to make your code more readable and maintainable. In assembly language where subroutines are identified by global labels, namespace can be achieved by using local labels.

Up until the last few tutorials we have been using global labels exclusively. This means that blocks of logic that essentially perform the same task needed a label with a unique identifier. A good example would be our “finished” labels. These were global in scope meaning when we needed to break out of a loop in one function we could jump to a “finished” label. But if we needed to break out of a loop in a different function we would need to name this same task something else maybe calling it “done” or “continue”. Being able to reuse the label “finished” would mean that someone reading the code would know that these blocks of logic perform almost the same task.

Local labels are prepended with a “.” at the beginning of their name for example “.finished”. You may have noticed them appearing as our code base in functions.asm grew. A local label is given the namespace of the first global label above it. You can jump to a local label by using the JMP instruction and the compiler will calculate which local label you are referencing by determining in what scope (based on the above global labels) the instruction was called.

Note: The file functions.asm was modified adding namespaces in all the subroutines. This is particularly important in the “slen” subroutine which contains a “finished” global label.

Updated functions.asm

;------------------------------------------

; int atoi(Integer number)

; Ascii to integer function (atoi)

atoi:

push rbx ; preserve rbx on the stack to be restored after function runs

push r8 ; preserve r8 on the stack to be restored after function runs

push rdx ; preserve rdx on the stack to be restored after function runs

push rsi ; preserve rsi on the stack to be restored after function runs

mov rsi, rax ; move pointer in rax into rsi (our number to convert)

mov rax, 0 ; initialise rax with decimal value 0

mov r8, 0 ; initialise r8 with decimal value 0

.multiplyLoop:

xor rbx, rbx ; resets both lower and uppper bytes of rbx to be 0

mov bl, [rsi+r8] ; move a single byte into rbx register's lower half

cmp bl, 48 ; compare rbx register's lower half value against ascii value 48 (char value 0)

jl .finished ; jump if less than to label finished

cmp bl, 57 ; compare rbx register's lower half value against ascii value 57 (char value 9)

jg .finished ; jump if greater than to label finished

sub bl, 48 ; convert rbx register's lower half to decimal representation of ascii value

add rax, rbx ; add rbx to our interger value in rax

mov rbx, 10 ; move decimal value 10 into rbx

mul rbx ; multiply rax by rbx to get place value

inc r8 ; increment r8 (our counter register)

jmp .multiplyLoop ; continue multiply loop

.finished:

cmp r8, 0 ; compare r8 register's value against decimal 0 (our counter register)

je .restore ; jump if equal to 0 (no integer arguments were passed to atoi)

mov rbx, 10 ; move decimal value 10 into rbx

div rbx ; divide rax by value in rbx (in this case 10)

.restore:

pop rsi ; restore rsi from the value we pushed onto the stack at the start

pop rdx ; restore rdx from the value we pushed onto the stack at the start

pop r8 ; restore r8 from the value we pushed onto the stack at the start

pop rbx ; restore rbx from the value we pushed onto the stack at the start

ret

;------------------------------------------

; void iprint(Integer number)

; Integer printing function (itoa)

iprint:

push rax ; preserve rax on the stack to be restored after function runs

push r8 ; preserve r8 on the stack to be restored after function runs

push rdx ; preserve rdx on the stack to be restored after function runs

push rsi ; preserve rsi on the stack to be restored after function runs

mov r8, 0 ; counter of how many bytes we need to print in the end

.divideLoop:

inc r8 ; count each byte to print - number of characters

mov rdx, 0 ; empty rdx

mov rsi, 10 ; mov 10 into rsi

idiv rsi ; divide rax by rsi

add rdx, 48 ; convert rdx to it's ascii representation - rdx holds the remainder after a divide instruction

push rdx ; push rdx (string representation of an intger) onto the stack

cmp rax, 0 ; can the integer be divided anymore?

jnz .divideLoop ; jump if not zero to the label divideLoop

.printLoop:

dec r8 ; count down each byte that we put on the stack

mov rax, rsp ; mov the stack pointer into rax for printing

call sprint ; call our string print function

pop rax ; remove last character from the stack to move esp forward

cmp r8, 0 ; have we printed all bytes we pushed onto the stack?

jnz .printLoop ; jump is not zero to the label printLoop

pop rsi ; restore rsi from the value we pushed onto the stack at the start

pop rdx ; restore rdx from the value we pushed onto the stack at the start

pop r8 ; restore r8 from the value we pushed onto the stack at the start

pop rax ; restore rax from the value we pushed onto the stack at the start

ret

;------------------------------------------

; void iprintLF(Integer number)

; Integer printing function with linefeed (itoa)

iprintLF:

call iprint ; call our integer printing function

push rax ; push rax onto the stack to preserve it while we use the rax register in this function

mov rax, 0Ah ; move 0Ah into rax - 0Ah is the ascii character for a linefeed

push rax ; push the linefeed onto the stack so we can get the address

mov rax, rsp ; move the address of the current stack pointer into rax for sprint

call sprint ; call our sprint function

pop rax ; remove our linefeed character from the stack

pop rax ; restore the original value of rax before our function was called

ret

;------------------------------------------

; int slen(String message)

; String length calculation function

slen:

push rdi

mov rdi, rax

.nextchar:

cmp byte [rax], 0

jz .finished

inc rax

jmp .nextchar

.finished:

sub rax, rdi

pop rdi

ret

;------------------------------------------

; void sprint(String message)

; String printing function

sprint:

push rdx

push rsi

push rdi

push rax

call slen

mov rdx, rax

pop rax

mov rsi, rax

mov rdi, 1

mov rax, 1

syscall

pop rdi

pop rsi

pop rdx

ret

;------------------------------------------

; void sprintLF(String message)

; String printing with line feed function

sprintLF:

call sprint

push rax

mov rax, 0Ah

push rax

mov rax, rsp

call sprint

pop rax

pop rax

ret

;------------------------------------------

; void exit()

; Exit program and restore resources

quit:

mov rdi, 0

mov rax, 60

syscall

ret

namespace.asm

; Namespace

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 namespace.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 namespace.o -o namespace

; Run with: ./namespace

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .data

msg1 db 'Jumping to finished label.', 0h ; a message string

msg2 db 'Inside subroutine number: ', 0h ; a message string

msg3 db 'Inside subroutine "finished".', 0h ; a message string

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

subrountineOne:

mov rax, msg1 ; move the address of msg1 into rax

call sprintLF ; call our string printing with linefeed function

jmp .finished ; jump to the local label under the subrountineOne scope

.finished:

mov rax, msg2 ; move the address of msg2 into rax

call sprint ; call our string printing function

mov rax, 1 ; move the value one into rax (for subroutine number one)

call iprintLF ; call our integer printing function with linefeed function

subrountineTwo:

mov rax, msg1 ; move the address of msg1 into rax

call sprintLF ; call our string print with linefeed function

jmp .finished ; jump to the local label under the subrountineTwo scope

.finished:

mov rax, msg2 ; move the address of msg2 into rax

call sprint ; call our string printing function

mov rax, 2 ; move the value two into rax (for subroutine number two)

call iprintLF ; call our integer printing function with linefeed function

mov rax, msg1 ; move the address of msg1 into rax

call sprintLF ; call our string printing with linefeed function

jmp finished ; jump to the global label finished

finished:

mov rax, msg3 ; move the address of msg3 into rax

call sprintLF ; call our string printing with linefeed function

call quit ; call our quit function

~$ nasm -f elf64 namespace.asm

~$ ld -m elf_x86_64 namespace.o -o namespace

~$ ./namespace

Jumping to finished label.

Inside subroutine number: 1

Jumping to finished label.

Inside subroutine number: 2

Jumping to finished label.

Inside subroutine "finished".

lesson-18

Fizz Buzz

Firstly, some background

FizzBuzz is group word game played in schools to teach children division. Players take turns to count aloud integers from 1 to 100 replacing any number divisible by 3 with the word “fizz” and any number divisible by 5 with the word “buzz”. Numbers that are both divisible by 3 and 5 are replaced by the word “fizzbuzz”. This children’s game has also become a defacto interview screening question for computer programming jobs as it’s thought to easily discover candidates that can’t construct a simple logic gate.

Writing our program

There are a number of code solutions to this simple game and some languages offer very trivial and elegant solutions. Depending on how you choose to solve it, the solution almost always involves an if statement and possibly an else statement depending whether you choose to exploit the mathematical property that anything divisible by 5 & 3 would also be divisible by 3 * 5. Being that this is an assembly language tutorial we will provide a solution that involves a structure of two cascading if statements to print the words “fizz” and/or “buzz” and an else statement in case these fail, to print the integer as an ascii value. Each iteration of our loop will then print a line feed. Once we reach 100 we call our program exit function.

fizzbuzz.asm

; Fizzbuzz

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 fizzbuzz.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 fizzbuzz.o -o fizzbuzz

; Run with: ./fizzbuzz

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .data

fizz db 'Fizz', 0h ; a message string

buzz db 'Buzz', 0h ; a message string

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rsi, 0 ; initialise our checkFizz boolean variable

mov rdi, 0 ; initialise our checkBuzz boolean variable

mov r8, 0 ; initialise our counter variable

nextNumber:

inc r8 ; increment our counter variable

.checkFizz:

mov rdx, 0 ; clear the rdx register - this will hold our remainder after division

mov rax, r8 ; move the value of our counter into rax for division

mov rbx, 3 ; move our number to divide by into rbx (in this case the value is 3)

div rbx ; divide rax by rbx

mov rdi, rdx ; move our remainder into rdi (our checkFizz boolean variable)

cmp rdi, 0 ; compare if the remainder is zero (meaning the counter divides by 3)

jne .checkBuzz ; if the remainder is not equal to zero jump to local label checkBuzz

mov rax, fizz ; else move the address of our fizz string into rax for printing

call sprint ; call our string printing function

.checkBuzz:

mov rdx, 0 ; clear the rdx register - this will hold our remainder after division

mov rax, r8 ; move the value of our counter into rax for division

mov rbx, 5 ; move our number to divide by into rbx (in this case the value is 5)

div rbx ; divide rax by rbx

mov rsi, rdx ; move our remainder into rdi (our checkBuzz boolean variable)

cmp rsi, 0 ; compare if the remainder is zero (meaning the counter divides by 5)

jne .checkInt ; if the remainder is not equal to zero jump to local label checkInt

mov rax, buzz ; else move the address of our buzz string into rax for printing

call sprint ; call our string printing function

.checkInt:

cmp rdi, 0 ; rdi contains the remainder after the division in checkFizz

je .continue ; if equal (counter divides by 3) skip printing the integer

cmp rsi, 0 ; rsi contains the remainder after the division in checkBuzz

je .continue ; if equal (counter divides by 5) skip printing the integer

mov rax, r8 ; else move the value in r8 (our counter) into rax for printing

call iprint ; call our integer printing function

.continue:

mov rax, 0Ah ; move an ascii linefeed character into rax

push rax ; push the address of rax onto the stack for printing

mov rax, rsp ; get the stack pointer (address on the stack of our linefeed char)

call sprint ; call our string printing function to print a line feed

pop rax ; pop the stack so we don't waste resources

cmp r8, 100 ; compare if our counter is equal to 100

jne nextNumber ; if not equal jump to the start of the loop

call quit ; else call our quit function

~$ nasm -f elf64 fizzbuzz.asm

~$ ld -m elf_x86_64 fizzbuzz.o -o fizzbuzz

~$ ./fizzbuzz

1

2

Fizz

4

Buzz

Fizz

7

8

Fizz

Buzz

11

Fizz

13

14

FizzBuzz

16

17

lesson-19

Execute Command

Firstly, some background

The EXEC family of functions replace the currently running process with a new process, that executes the command you specified when calling it. We will be using the SYS_EXECVE function in this lesson to replace our program’s running process with a new process that will execute the linux program /bin/echo to print out “Hello World!”.

Naming convention

The naming convention used for this family of functions is exec (execute) followed by one or more of the following. https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man3/exec.3.html shows the convention information. In this case we are using execve which has 3 arguments.

int execve(const char *pathname, char *const argv[], char *const envp[]);

1 - Uses the PATH environment variable to find the file named in the path argument to be executed.

2 - Command-line arguments are passed to the function as an array of pointers.

3 - An array of pointers to environment variables is explicitly passed to the new process image.

Writing our program

We will need to pass our arguments in the following format: The first argument is a string containing the command to execute, then an array of arguments to pass to that command and then another array of environment variables that the new process will use. As we are calling a simple command we won’t pass any special environment variables to the new process and instead will pass 0h (null). Refer to this https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromiumos/docs/+/master/constants/syscalls.md#x86_64-64_bit . We will need to use system call 59 to call execve. This requires the 3 arguments to be put in the following registers rdi, rsi, and rdx. Also x86 assembly you could use dd size for pointer struct, however in x64 you have to use dq.

Both the command arguments and the environment arguments need to be passed as an array of pointers (addresses to memory). That’s why we define our strings first and then define a simple null-terminated struct (array) of the variables names. This is then passed to SYS_EXECVE. We call the function and the process is replaced by our command and output is returned to the terminal.

execute.asm

; Execute

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 execute.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 execute.o -o execute

; Run with: ./execute

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .data

command db '/bin/echo', 0h ; command to execute

arg1 db 'Hello World!', 0h

arguments dq command

dq arg1 ; arguments to pass to commandline (in this case just one)

dq 0h ; end the struct

environment dq 0h ; arguments to pass as environment variables (inthis case none) end the struct

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rdx, environment ; address of environment variables

mov rsi, arguments ; address of the arguments to pass to the commandline

mov rdi, command ; address of the file to execute

mov rax, 59 ; invoke SYS_EXECVE (kernel opcode 59)

syscall

call quit ; call our quit function

Note: Here are a couple other commands to try.

execute.asm

SECTION .data

command db '/bin/ls', 0h ; command to execute

arg1 db '-l', 0h

execute.asm

SECTION .data

command db '/bin/sleep', 0h ; command to execute

arg1 db '5', 0h

lesson-20

Process Forking

Firstly, some background

In this lesson we will use SYS_FORK to create a new process that duplicates our current process. SYS_FORK takes no arguments - you just call fork and the new process is created. Both processes run concurrently. We can test the return value (in rax) to test whether we are currently in the parent or child process. The parent process returns a non-negative, non-zero integer. In the child process RAX is zero. This can be used to branch your logic between the parent and child.

In our program we exploit this fact to print out different messages in each process.

Note: Each process is responsible for safely exiting.

fork.asm

; Fork

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 fork.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 fork.o -o fork

; Run with: ./fork

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .data

childMsg db 'This is the child process', 0h ; a message string

parentMsg db 'This is the parent process', 0h ; a message string

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rax, 57 ; invoke SYS_FORK (kernel opcode 57)

syscall

cmp rax, 0 ; if rax is zero we are in the child process

jz child ; jump if rax is zero to child label

parent:

mov rax, parentMsg ; inside our parent process move parentMsg into rax

call sprintLF ; call our string printing with linefeed function

call quit ; quit the parent process

child:

mov rax, childMsg ; inside our child process move childMsg into rax

call sprintLF ; call our string printing with linefeed function

call quit ; quit the child process

lesson-21

Telling the time

Generating a unix timestamp in NASM is easy with the SYS_TIME function of the linux kernel. Simply pass OPCODE 200 to the kernel with no arguments and you are returned the Unix Epoch in the EAX register.

That is the number of seconds that have elapsed since January 1st 1970 UTC.

time.asm

; Time

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 time.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 time.o -o time

; Run with: ./time

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .data

msg db 'Seconds since Jan 01 1970: ', 0h ; a message string

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rax, msg ; move our message string into rax for printing

call sprint ; call our string printing function

mov rax, 200 ; invoke SYS_TIME (kernel opcode 200)

syscall ; call the kernel

call iprintLF ; call our integer printing function with linefeed

call quit ; call our quit function

lesson-22

File Handling - Create Firstly, some background

File Handling in Linux is achieved through a small number of system calls related to creating, updating and deleting files. These functions require a file descriptor which is a unique, non-negative integer that identifies the file on the system. Writing our program

We begin the tutorial by creating a file using sys_creat. We will then build upon our program in each of the following file handling lessons, adding code as we go. Eventually we will have a full program that can create, update, open, close and delete files.

sys_creat expects 2 arguments - the file permissions in RSI and the filename in RDI. The sys_creat opcode is then loaded into RAX and the kernel is called to create the file. The file descriptor of the created file is returned in RAX. This file descriptor can then be used for all other file handling functions.

create.asm

; Create

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 create.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 create.o -o create

; Run with: ./create

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .data

filename db 'readme.txt', 0h ; the filename to create

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rsi, 0777o ; set all permissions to read, write, execute

mov rdi, filename ; filename we will create

mov rax, 85 ; invoke SYS_CREAT (kernel opcode 85)

syscall ; call the kernel

call quit ; call our quit function

lesson-23

File Handling - Write

Building upon the previous lesson we will now use sys_write to write content to a newly created file.

sys_write expects 3 arguments - the number of bytes to write in RDX, the contents string to write in RSI and the file descriptor in RDI. The sys_write opcode is then loaded into RAX and the kernel is called to write the content to the file. In this lesson we will first call sys_creat to get a file descriptor which we will then load into RDI.

write.asm

; Write

; Compile with: nasm -f elf64 write.asm

; Link with: ld -m elf_x86_64 write.o -o write

; Run with: ./write

%include 'functions.asm'

SECTION .data

filename db 'readme.txt', 0h ; the filename to create

contents db 'Hello world!', 0h ; the contents to write

SECTION .text

global _start

_start:

mov rsi, 0777o ; code continues from lesson 22

mov rdi, filename

mov rax, 85

syscall

mov rdx, 12 ; number of bytes to write - one for each letter of our contents string

mov rsi, contents ; move the memory address of our contents string into rsi

mov rdi, rax ; move the file descriptor of the file we created into rdi

mov rax, 1 ; invoke SYS_WRITE (kernel opcode 1)

syscall ; call the kernel

call quit ; call our quit function

After compiling and running. Cat command will show the contents of file

$ nasm -f elf64 write.asm

$ ld -m elf_x86_64 write.o -o write

$ ./write

$ cat readme.txt

Hello world!

lesson-24

File Handling - Open